A Display of Stoic Quotes using Arduino and e-Paper Display

Some time ago, I was experimenting with e-paper displays and built a prototype that would use an API to retrieve a quote (from my favorite stoic philosophers). Because I was calling an API, it was a good excuse to test the Device Flow authentication that Auth0 supports.

This weekend, I thought about building a standalone display. After all, these boards come with a ton of memory, but of different kinds. Arduinos use Harvard architecture and use different memory systems for programs and data. At least some do. This particular board I’m using has 256KB of flash memory (!), which is used for the program, but can easily be used for constant content (e.g. string). Which is exactly what I need, storing a lot of strings: quotes. Compare this to 32KB of RAM…it is a lot more.

Arduinos have 3 types of memory: Flash memory, where the program is stored, SRAM for variables and EEPROM, for long term storage. More info here

In some sketches, you can use the PROGMEM directive, but in some more modern SDKs, the compiler is smart enough to move everything const to Flash, and all standard library functions will know how to deal with it (e.g. strcpy, strcmp, etc.)

const char * marcus_aurelius[] = {

"The best revenge is not to do as they do.",

"Today I escaped all circumstance, or rather I cast out all circumstance, for it was not outside me, but within my judgments.",

"Kindness is invincible.",

"Accustom yourself not to be disregarding of what someone else has to say: as far as possible enter into the mind of the speaker.",

"...life is a warfare and a stranger's sojourn, and after-fame is oblivion.",

// may more lines here

};

All the strings in the marcus_aurelius variable are all stored in Flash by qualifying the variable with const.

Needless to say, you cannot write on

constvariables.

The data structures for quotes

I wanted to stash as many quotes as possible, from many different authors, and initialize all in an easy way, so I came up with this structure:

#include "Epictetus.h"

#include "Seneca.h"

#include "Zeno.h"

#include "Aurelio.h"

typedef struct {

const int length;

const char ** quotes;

const char * author;

} QUOTES;

const QUOTES quotes[] = {

{

.length = sizeof(seneca)/sizeof(char *),

.quotes = &seneca[0],

.author = "Seneca"

},

{

.length = sizeof(zeno)/sizeof(char *),

.quotes = &zeno[0],

.author = "Zeno"

},

{

.length = sizeof(aurelio)/sizeof(char *),

.quotes = &aurelio[0],

.author = "Marcus Aurelius"

},

{

.length = sizeof(epictetus)/sizeof(char *),

.quotes = &epictetus[0],

.author = "Epictetus"

}

};

Each of the #include at the top is simply const char * [] with (hundreds) of quotes. Common functions to work with it are easily implemented and remain the same regardless of adding new authors.

int totalQuotesAvailable(){

int totalQuotes = 0;

for(int x = 0; x < sizeof(quotes)/sizeof(QUOTES); x++){

totalQuotes += quotes[x].length;

}

return totalQuotes;

}

For picking up a random quote, I write this algorithm:

CURRENTQUOTE currentQuote;

CURRENTQUOTE * getCurrentQuote(){

int max = totalQuotesAvailable();

int randomIndex = random(0, max);

int block = -1;

do{

block++;

randomIndex -= quotes[block].length;

}while(randomIndex >= 0);

strcpy(currentQuote.quote, quotes[block].quotes[randomIndex*-1]);

strcpy(currentQuote.author, quotes[block].author);

return ¤tQuote;

}

where CURRENTQUOTE is a simple structure:

typedef struct {

char author[MAX_AUTHOR];

char quote[MAX_QUOTE];

} CURRENTQUOTE;

The main loop simply sleeps for a while and then calls getCurrentQuote:

void showQuote(){

CURRENTQUOTE * q = quote.getCurrentQuote();

const char * info = getInfoLabel();

printer.Init();

printer.PrintQuote(q->quote, q->author, info);

printer.Sleep();

}

printeris just an abstraction built around the e-Paper display.infois a subtitle.

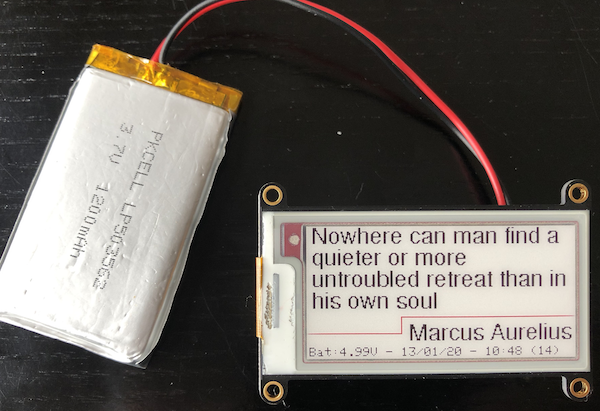

The result shows this:

Storage

I was surprised by the number of quotes I was able to stash into this little device. My limiting factor actually became the display. Because, even when using a small font, it is limited to the length of the text it is able to display. Now that I think about it, a scrolling display would be a nice followup project.

Anyway, I added approximately 1200 quotes, with less than 150 characters each. The Arduino compiler reports 70% of program memory used, which makes sense. 70% of program use is about 183K bytes. If I comment out all the constant strings, the compilation ends with a 70K image. Which means the average quote is 95 bytes long.

1200 provides for quite a bit of cycling before it repeats itself.

Getting fancy

As you see on the screenshot, the display shows the main quote, the author and a bunch of other information:

- The battery voltage

- The date & time

- A count (between parenthesis)

The battery voltage was very simple, as this is supported in the board I’m using: a simple analog input. Displaying Date & Time was a good opportunity to use the Real Time Clock that is also included in Arduino

I needed a good way of synchronizing the clock with a good source. But, as it happens often, Arduino is one step ahead of me. The WiFi class includes a getTime method that will automagically retrieve the time using NTP.

The

WiFi101uses the wifi’s firmware under the hood. It usestime-c.nist.govandtime-d.nist.govas NTP servers, and this is not configurable.

unsigned long Clock_Init(){

int status = WL_IDLE_STATUS;

if (WiFi.status() == WL_NO_SHIELD) {

Debug("Clock. WiFi shield not present");

return 0;

}

unsigned long epoch = 0;

int numberOfTries = 0, maxTries = 6;

// attempt to connect to WiFi network:

while( status != WL_CONNECTED){

if(numberOfTries == maxTries){

return 0; // Failed

}

status = WiFi.begin(WIFI_SSID, WIFI_PWD);

delay(5000);

numberOfTries++;

}

rtc.begin();

numberOfTries = 0;

do {

Debug("Clock. Getting time with WiFi");

epoch = WiFi.getTime();

numberOfTries++;

}while ((epoch == 0) && (numberOfTries < maxTries));

WiFi.disconnect();

if(numberOfTries == maxTries){

Debug("Clock. NTP unreachable.");

} else {

int tz = TZ;

epoch += tz*60*60;

rtc.setEpoch(epoch);

}

return epoch;

}

As long as you don’t lose power, the RTC will continue to keep track of time, and it is super easy to extract and pretty-print information:

char time[MAX_TIME_STRING];

char * Clock_CurrentDateTime(){

sprintf(time, "%d/%02.2d/%02.2d - %d:%02.2d", rtc.getDay(), rtc.getMonth(), rtc.getYear(), rtc.getHours(), rtc.getMinutes());

return time;

}

Notice the adjustment for TZ. Because

epochis seconds, I’m just subtracting (or adding) the number of hours. For exampleTZ=-8would equalGMT-8(PST).

A nice side effect of using the RTC is that we can program an alarm to refresh the display at certain intervals. RTCZero (the Arduino library) is quite flexible and allows you to set up somewhat arbitrary triggers (not as powerful as cron, but still…). But the most important consequence of this is that it frees up the loop function to do other things. Now refreshing the display will happen on an interrupt handler.

In my case, I wanted the display refreshed every 5 min, so I’m using:

rtc.setAlarmSeconds(1);

rtc.enableAlarm(rtc.MATCH_SS); //every '01' seconds -> every minute

rtc.attachInterrupt(alarmHandler);

and then:

void alarmHandler(){

if(refresh_runs-- == 0){

refresh_runs = RefreshMinutes;

if(handler){

runs++;

(*handler)();

}

}

}

handler is wired up to showQuote.

I originally had showQuote wired up directly to the alarm handler. But this runs as part of an ISR (Interrupt Service Routine). And this sometimes causes issues. So I decided to decouple it and just have the ISR set a flag that then the main loop would pick. The rate of interrupts are very low, so this all should work without issues of race conditions, etc. I’m updating the display in intervals of 10 - 30 mins.

What to do with all time we’ve got in between interrupts?

Now that refreshing the display takes care of itself, I decided it would be fun to create a command-line interface for the display to interact with a user. After all, there’s no touch screen, no buttons, nothing… it’d be cool to be able to configure WiFi, refresh frequency, etc. via a terminal.

All this will be the subject of a future post.